We pay tribute to the Sinclair ZX Spectrum – a computer that created an entire ecosystem of programmers, publishers, hardware makers, and gamers.

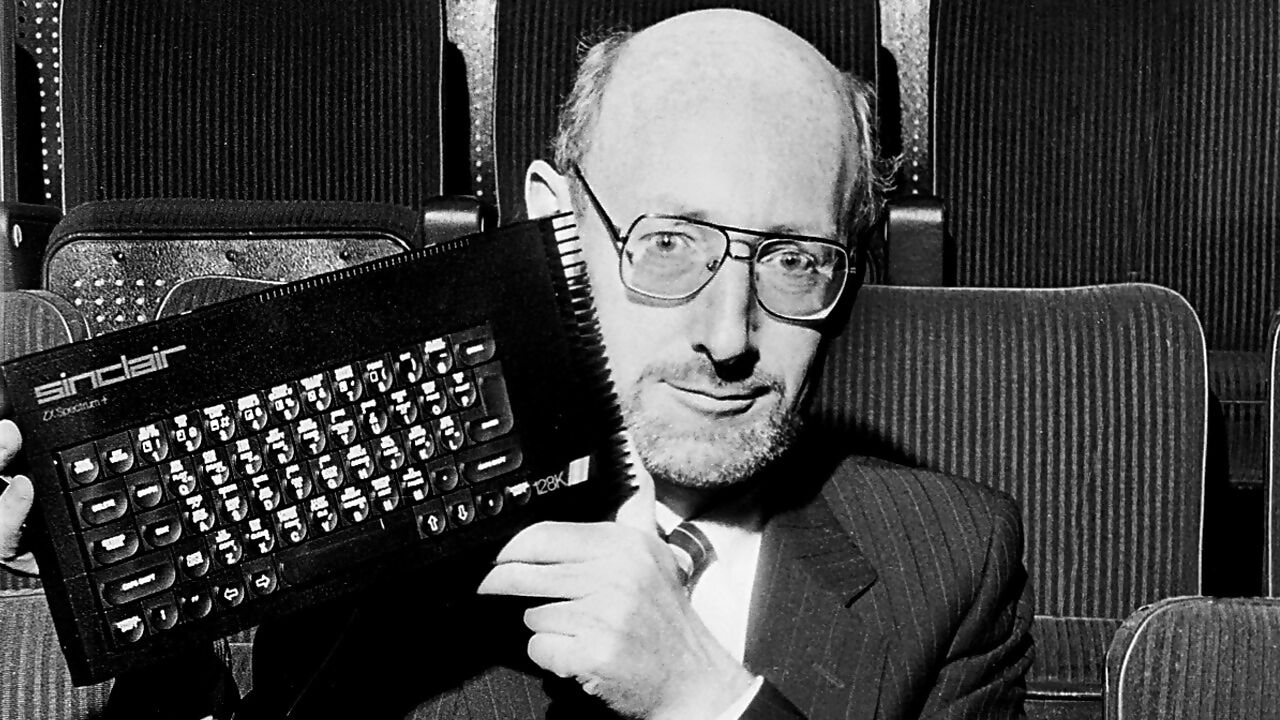

One cold Christmas in 1977, Mel Croucher was at a house party somewhere in Cambridge. Wandering into the kitchen, Croucher encountered a tall man wearing large round spectacles, his bald head fringed with a thin halo of red hair. “We fell to talking about a forthcoming consumer opportunity for microcomputers,” Croucher recalls. “He told me that the purpose of home computers was to conduct personal accounts, solve mathematical problems, and make inventories.”

At this point, Croucher had recently already set up what is widely credited as the first video games company in the UK, Automata, which made titles for the Commodore PET. That December, Croucher used a local radio station to broadcast a blast of data, which listeners could then record onto audio cassette and load into their computer. With this in mind, Croucher was openly amused by the bespectacled party-goer’s argument that computers were for boring things like accounts. “I told him that the purpose of home microcomputers was to be very silly and play games,” Croucher says. “He looked at me as if I was bonkers, which indeed I was.”

Not long after this exchange, the bespectacled man made his excuses and headed for the bathroom. Puzzled, Croucher tapped another party-goer on the shoulder and asked “who that miserable bald bloke with the shiny round specs was.”

“Him?” the party-goer replied. “Don’t mind him – that’s Clive Sinclair.”

“A wee while later,” Croucher says now, “the Sinclair ZX Spectrum changed the world for everybody at that party, and a whole bunch of people beyond.”

For a generation that used it, the ZX Spectrum was the gateway into a whole new medium. At a time when computing was insanely expensive, it brought programming and video games within the reach of just about everyone. And then there were the indelible memories it left behind. The clunk and click of a cassette going into a player. The bleep and chirp as games loaded – slowly – from yards of unspooling audiotape. The fleshy quality of the first generation computer’s keys. Its instantly recognisable palette of 15 garish colours.

Ocean Software was among the biggest publishers for the ZX Spectrum. Its RoboCop tie-in was a massive hit, and triggered a wave of similar games based on films.

On its launch in 1982, though, the ZX Spectrum was still just the latest in a long line of products from Cambridge’s Sinclair Research Limited. Headed up by the inventive, irascible figure of Sir Clive Sinclair, the firm had already made its mark with pioneering digital calculators, radios, and a few earlier low-cost computers: the MK14, ZX80, and ZX81, which could all be bought either pre-built or in kit form. Those were highly successful machines (the ZX81 alone sold around 1.5 million units), but ones largely enjoyed by hobbyists. With the ZX Spectrum, Sinclair was aiming to create a computer for the masses: a machine which, as Croucher was told at that party five years earlier, could be used by owners of small businesses to run their accounts, or by weary parents who wanted to track their household budgets. The ZX Spectrum wasn’t the most capable computer available at the time, but it was far cheaper than its rivals – it retailed at just £125 in 1982, making it one of the most affordable computers available in the UK.

The ZX Spectrum was a huge seller (around five million units sold worldwide, all told), such that Sinclair received a knighthood for his business achievements in 1983. What he hadn’t foreseen, though, was just who would flock to buy his computer. The Spectrum largely failed to appear in the corners of dusty offices; the computer wasn’t used so much by parents as their kids: a generation of eager youngsters who sat in their bedrooms and began programming their own games.

It was here that one of the ZX Spectrum’s technical limitations proved to be a masterstroke. The computer’s default medium was the humble audio cassette – a format that was painfully slow to load and save data when compared to a floppy disk, it was also delicate and potentially unreliable. The advantage the audio cassette did have, though, was affordability: most people had a tape recorder in their houses in the 1980s, and so they could easily connect it to their Spectrum with a couple of leads (until the ZX Spectrum +2, launched in 1986, the computer wasn’t sold with a tape deck).

All of this meant that an entire games industry quickly built up around the ZX Spectrum, with lone programmers quite able to make a game, get a few cassettes duplicated, maybe make a photocopied inlay, and sell it through the classified section in newspapers or magazines. Before long, an entire community had built up around the ZX Spectrum: developers, publishers, and magazines dedicated to its growing library of games. It was impressive stuff, particularly given that Sinclair himself never thought of the Spectrum as a games machine: early magazine ads pushed its ease of programming, range of peripherals – including the diminutive ZX Printer – and affordable price (£125 for the 16K model and £175 for the 48K edition).

Programming twins Philip and Andrew Oliver still have an original ZX Spectrum in its box.

“The trick of designing 8-bit computers was giving developers a way of getting the most out of every little bit of memory and processing power,” says Philip Oliver, who with his twin brother Andrew coded some of the most popular games for the ZX Spectrum. “Sinclair got the formula just right with the Spectrum, and as a result, it was great computers for very varied games. Bizarrely, Sinclair wasn’t trying to make a games computer. His adverts didn’t even mention games! It was the school playground, early game publishers, and the gaming magazines that did the real marketing for the Spectrum!”

Mel Croucher’s Automata, which had moved from the Commodore PET to making games for the ZX81, was soon making some of the most innovative games for the ZX Spectrum by 1983. Pimania and My Name Is Uncle Groucho, You Win A Big Fat Cigar mixed video games with real-world adventuring, and physical prizes for the first people who could complete them. Then there was Deus Ex Machina: a kind of interactive prog rock album, with Ian Dury and Jon Pertwee providing voices.

As the video game market matured, games moved from being sold via classified ads and small conventions to major stores like Boots and WH Smith. It was the first clue that video games were truly becoming mainstream. All the same, many of the earlier games programmed for the ZX Spectrum retained a uniquely British flavour; Skool Daze was a slice-of-life adventure about a kid trying to steal his less-than-glowing school report from the headmaster’s office. Wanted: Monty Mole, the first in a series of furry platformers, was inspired by the mid-1980s miners’ strike.

“In my overly long experience, I have never known such a creative time for the British games industry as the early 1980s,” Croucher tells us. “The progress we made and the originality we force-fed the public has never been bettered since. Everything the global market takes for granted now was founded then in terms of concepts, protocols, and coding, all right here in our bedrooms and garages, and all without any involvement with the corporates.”

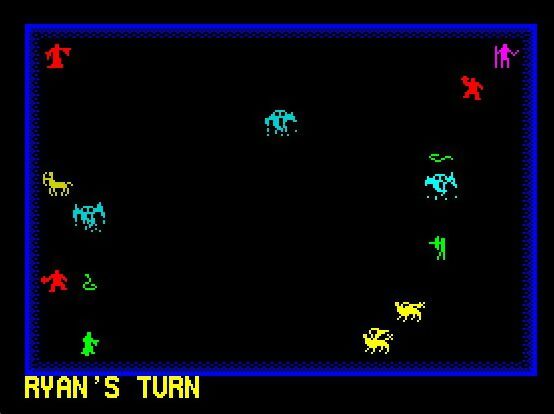

Another Julian Gollop classic, Chaos. When played with a group of friends, this turn-based wizard-’em-up truly lived up to its title.

At the time, many of the people developing these games weren’t a great deal older than the kids playing them. Eugene Evans, the young co-founder of Liverpool’s Imagine Software, leapt to national attention when newspapers began to report that his programming prowess had turned him into a sports car-owning prodigy with a reported annual salary of £35,000 a year. In reality, the Evans story was all so much marketing hot air, but it was emblematic of a new industry whose possibilities seemed limitless. Magazines often ran adverts from publishers looking for new games in exchange for cash; young designers like Matthew Smith, creator of Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, were certainly doing well – if not exactly becoming millionaires – from the sales of their games.

Philip and Andrew Oliver, two kids from the West Country who started making games while they were still at school, had first begun programming on the Dragon 32 earlier in the 1980s. By the end of the decade, though, the Olivers had become arguably the most prolific programmers for the ZX Spectrum, having made the likes of Dizzy and its assorted sequels and spin-offs, and such titles as Advanced Pinball Simulator and Grand Prix Simulator for publisher Codemasters. “The low cost of the Spectrum and diverse catalogue games made it an affordable computer that inspired a generation of players and game developers,” says Philip Oliver. “This created the perfect ecosystem for the British games industry to grow.”

As the ZX Spectrum scene burgeoned, so too did the magazines that covered it, which soon evolved from stuffy hobbyist tomes to less formal publications that reflected their young, enthusiastic readership. Your Sinclair, for example, had begun life as the more serious Your Spectrum, but by the late-1980s, had grown into an entertainingly anarchic publication with its own unique sense of humour. Buying a copy of Your Sinclair in its heyday was like joining a particularly friendly club: there were reviews and previews, as you’d expect, but then there were odd, surprising things like tabloid-style photo-stories, little cartoons, or letters pages full of curious observations from readers.

Deathchase – often called 3D Deathchase – managed to wring a fast-paced and exciting shooter out of the Spectrum’s 3.5MHz processor.

“It certainly reflected the types of people who read the magazine and interacted with the YS team on the regular,” recalls Matt Bielby, who edited Your Sinclair from 1989 to 1991. “The letters page was extremely fun to do, as opening each day’s post was always a bit of an adventure – you never knew what you were going to get. I loved the challenge of working with illustrators for the covers, and the thrill of getting the final painting in the post – a nerve-racking moment, as you never had the time or budget to replace whatever it was they’d done, so you really were at their mercy. And I loved the individual brilliance of some of our contributors. When Duncan MacDonald did a script for a photo love story, or Whistlin’ Rick Wilson recorded the sweetest love song to fill up the end of a cover tape, you’d find me grinning from ear to ear.”

While the games industry continued to grow through the late 1980s, however, the ZX Spectrum itself remained relatively static. The ZX Spectrum 128 belatedly emerged in 1985, upping the computer’s RAM and adding a heatsink to the side, but Sir Clive seemed more smitten by the Sinclair QL: a high-end computer that, with a retail price of £399, was intended as the fancier counterpart to the ZX Spectrum. It wouldn’t be a silly games machine like the Speccy, but instead, a deluxe business machine designed to compete with Apple and IBM’s offerings. Released in 1984, the QL was a commercial failure, was discontinued in 1986, by which point the Sinclair brand had been purchased by Alan Sugar’s rival firm, Amstrad.

The ZX Spectrum continued to evolve outwardly at its new home; the +2 featured a revised keyboard and integrated tape player; the +3 was the same again but with a 3-inch disk drive replacing the tape player. There was also a +2A, which, just to confuse everybody, was a +3 but with a tape player replacing the disk drive. Meanwhile, the ZX Spectrum even gained a foothold overseas, with the system enjoying a certain success in Spain and Portugal thanks to Timex’s iterations of the machine for those markets, while unofficial clones emerged in eastern Europe and the USSR.

The Olivers programmed dozens of titles for the ZX Spectrum. Dizzy and its sequels are perhaps the most fondly remembered.

What never emerged, though, was a true, next-generation successor to the ZX Spectrum. The Speccy’s playground rival, the Commodore 64, got the 16-bit Amiga 500 in 1987, which soon became one of the best-selling computers for playing games in the UK. The closest the ZX Spectrum got to a follow-up was the SAM Coupé, a stylish-looking machine introduced in 1989 by a company called Miles Gordon Technology. It was compatible with the Spectrum, and with a faster CPU and more memory, could have been considered its logical successor. It was still an 8-bit computer at heart, though, making it wildly off-pace compared to the Amiga, and it was ultimately discontinued in 1992 following poor sales.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s hard not to wonder what might have happened had Sinclair put his restless energy into making a true ZX Spectrum follow-up: one that recaptured its ease of programming and affordability, but in a package that could compete more directly with the Commodore Amiga. “Would it have been a hit? Perhaps, if it had been cheap and accessible enough,” Matt Bielby says. “But Sinclair didn’t feel like a company that had it in it to create a dynasty of products, like Apple has. The approach seemed more scattershot, with occasional hits and as many brave failures.”

From the mid-1980s onwards, it was those brave failures that Sir Clive Sinclair would become widely known for: the C5, his noble yet somewhat undercooked electric vehicle, became the butt of jokes for years in the British media. Even add-ons for the ZX Spectrum, which might have enjoyed the benefit of its broad install base, struggled to take root: the ZX Microdrive, for example, was intended as a cheaper medium than a conventional floppy disk, but it was still tape-based, like a cassette, and ultimately proved unreliable.

Before the big publishers started moving in later in the 1980s, Spectrum games – like Wanted: Monty Mole, shown here – often had a palpably British feel.

What’s undeniable, though, is just how long lasting and loyal the ZX Spectrum’s following remained. Sir Clive Sinclair may have come to resent his association with what had become a games machine, but its popularity remained strong over a decade after its initial launch. Even as the Amiga market grew in the early 1990s, games were still being made and enjoyed on the ZX Spectrum. Gradually, though, the magazines grew thinner as the 1990s went on; Crash was swallowed up by Sinclair User, which in turn ended its run in April 1993. Your Sinclair published its final issue that September. By this point, Matt Bielby had moved onto other magazines, including Amiga Power, Super Play, and Total Film, but the spirit of the ZX Spectrum and Your Sinclair remained with him long afterwards. “Part of the YS ethos – if somewhat disguised – remained with SFX and Total Film and whatever else. The idea we should always try harder than our rivals, attempt to be funnier, and embrace original ideas came from YS as much as it came from anywhere. I like a magazine that can surprise you, and there was always an element of surprise to Your Sinclair.”

More broadly, the ZX Spectrum’s impact on the British games industry has lingered, too. Some of its biggest names – Chris and Tim Stamper, whose studio Ultimate Play the Game later became Rare, XCOM designer Julian Gollop – first began making games on the Speccy. When Sir Clive Sinclair sadly passed away at the age of 81 on 16 September 2021, his contribution to computing and the games industry was widely – and deservedly – singled out for praise. The ZX Spectrum’s impact was, Bielby argues, “Absolutely huge. It was so accessible and adaptable, and it encouraged a slightly anarchic, punky, do-it-yourself approach to gaming. And it gave so many people access to technology they could never have afforded otherwise. Really, it was crucial.”

“Many of us owe our careers to Sir Clive,” concurs Eben Upton, creator of the Raspberry Pi, “either directly, having grown up programming the Spectrum, or indirectly, having grown up with the BBC Micro – Chris Curry of course having famously been a Sinclair employee before founding Acorn. Cambridge today is full of people and companies that can trace their heritage one way or another to Sinclair Radionics or Sinclair Research.”

Skool Daze was quite ahead of its time: it was essentially a miniature sandbox where you could roam the school grounds, causing trouble as you saw fit.

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a games industry without the ZX Spectrum. “Oh, it would have been very different,” says YouTuber and former Wireframe columnist Kim Justice, whose channel is a trove of stories about the British computing boom. “It probably would have been a lot harder for folks to get into, seeing as one of the big things about these computers was the low cost of entry. You could even argue that the world of computers would have looked completely different, seeing as Atari’s Jack Tramiel was inspired to make a budget computer from Sinclair’s systems. I think there’d have certainly been a lot less people making games, which would be a shame – you got a lot of character from Speccy games that were quite unique to it.”

“Look around – look at the people who have stepped on its shoulders, and how people have stepped onto their shoulders in turn,” says Simon Brew, who edited Micro Mart magazine between 2000 and 2011. “It started a cycle that I don’t see stopping. Personally, the Spectrum is the reason I’m here. The Spectrum didn’t just get me into computing, it got me into magazines.”

“Sir Clive was the quintessential British boffin,” adds Philip Oliver. “But he was also flawed when it came to business, marketing, and his inability to see games as the route to his success. Like many, including Steve Jobs, games were seen as a frivolous use of their powerful computers. We were obsessed with making games and wanted to meet Sir Clive at a game show, but he never attended them, so we never met him.”

After that random encounter in 1977, Mel Croucher never got to meet Sir Clive Sinclair again, either. But like so many of us, he owes a debt of gratitude to the inventor who unwittingly helped create the British games industry. “While Clive Sinclair was alive, I never apologised for my sin of laughing at him, and I never thanked him for his gift to us all,” Croucher says. “So here goes. Sorry Clive, even though I was right and you were wrong. You enabled us all to be very silly and play games, and I am forever thankful to you.”

This article was originally published in Wireframe #56.