Difficulty used to be simple. Some games offered a selection of predefined settings to suit different skill levels; some offered nothing. Many were intentionally punishing – either because they were made for coin-hungry arcade machines, or because they weren’t very big, and wouldn’t last long if they didn’t keep sending you back to the start. Anyone who didn’t fancy their arbitrarily defined challenges would have to admit defeat.

As much as gaming has evolved since its primitive beginnings, its conceptions of challenge often still have a foot in the past. Most games are more customisable now, and are at least designed to be finished. But until recently, few have moved beyond traditional difficulty levels to explore how challenge affects our engagement, or consider more effective ways for players to balance their satisfaction. Nor has the larger gaming community fully discarded the implied stigma of taking the ‘easy’ option or ‘cheating’.

Increasingly in the last few years, however, tentative advances have turned into radical rethinks, as developers have dissected the notion of challenge, exploring its value beyond merely measuring prowess. Whether or not these studios make games that are taxing by default, they’re continually adapting to feedback, exploring the emotional power of difficulty, or posing questions about the flexibility of authored experiences. Difficulty has become complex, and better for it.

ASSIST LEADER

The poster child for this new wave is undoubtedly 2018’s Celeste. “The biggest shift for me has been understanding difficulty as unique to everyone who plays a game, rather than something the designer is carving into stone,” the game’s creator, Maddy Thorson, tells us. Celeste does offer a prescribed challenge, and a stiff one at that, designed to flow in tune with the emotional journey of protagonist Madeline as she climbs a mystical mountain while dealing with self-doubt, anxiety, and depression. Yet it also includes an ‘assist mode’ that allows players to strip away layers of difficulty, say, reducing the game’s speed, or making Madeline invincible.

Assist mode was initially a controversial inclusion for Thorson herself. “When it was discussed, I was the team member who was most against it,” she says. “It felt like a betrayal of the precious experience I was designing.” It’s easy to understand this reaction, given how much work went into balancing Celeste’s difficulty. “First, you need to define what the ‘right’ balance even means for the level you’re building,” Thorson says. With Celeste, that meant aligning it with the narrative. “We start by trying to define what ‘problem’ we’re solving, then solve it by making the level. From there, it comes down to playtesting to confirm that the player’s experience is aligning with our intentions.”

Screens in Celeste often appear intimidating, increasing the sense of achievement when you survive them.

The issue then was how to account for the variance in ability between potential players. “As we got to the point where we could see how the game’s narrative was resolving,” Thorson says, “and I had seen people of different skill levels play much of the game, it began to feel obvious that the assist mode would be a positive addition if we did it with care.” By that stage, there were already means for players to adjust the difficulty upwards, by chasing tricky collectable strawberries or attempting the tough ‘B-sides’ of each level, so it made sense to offer something in the opposite direction. “Players can pick and choose when to go for that extra challenge and when to ignore it,” says Thorson. “I’ve come to see assist mode as an extension of that, implemented in a more explicit way and covering the lower end of the difficulty spectrum.”

Assist mode was also more efficient to implement than a traditional difficulty select. “We felt the only way to do that well in Celeste would be to redesign and retest all of the levels for each difficulty category, which made it an unworkable solution,” Thorson says. “We also chose assists for maximal impact for the player but minimal consequences to the system.”

It’s no surprise, then, that for their next game, Earthblade, Thorson and her team are already thinking about flexible difficulty, although it’s not yet clear whether Earthblade will have a specific assist mode. “Difficulty is an ever-present consideration for us,” Thorson says. “Celeste taught us a lot about difficulty, and we want to carry those lessons forward in whatever way fits best into Earthblade.”

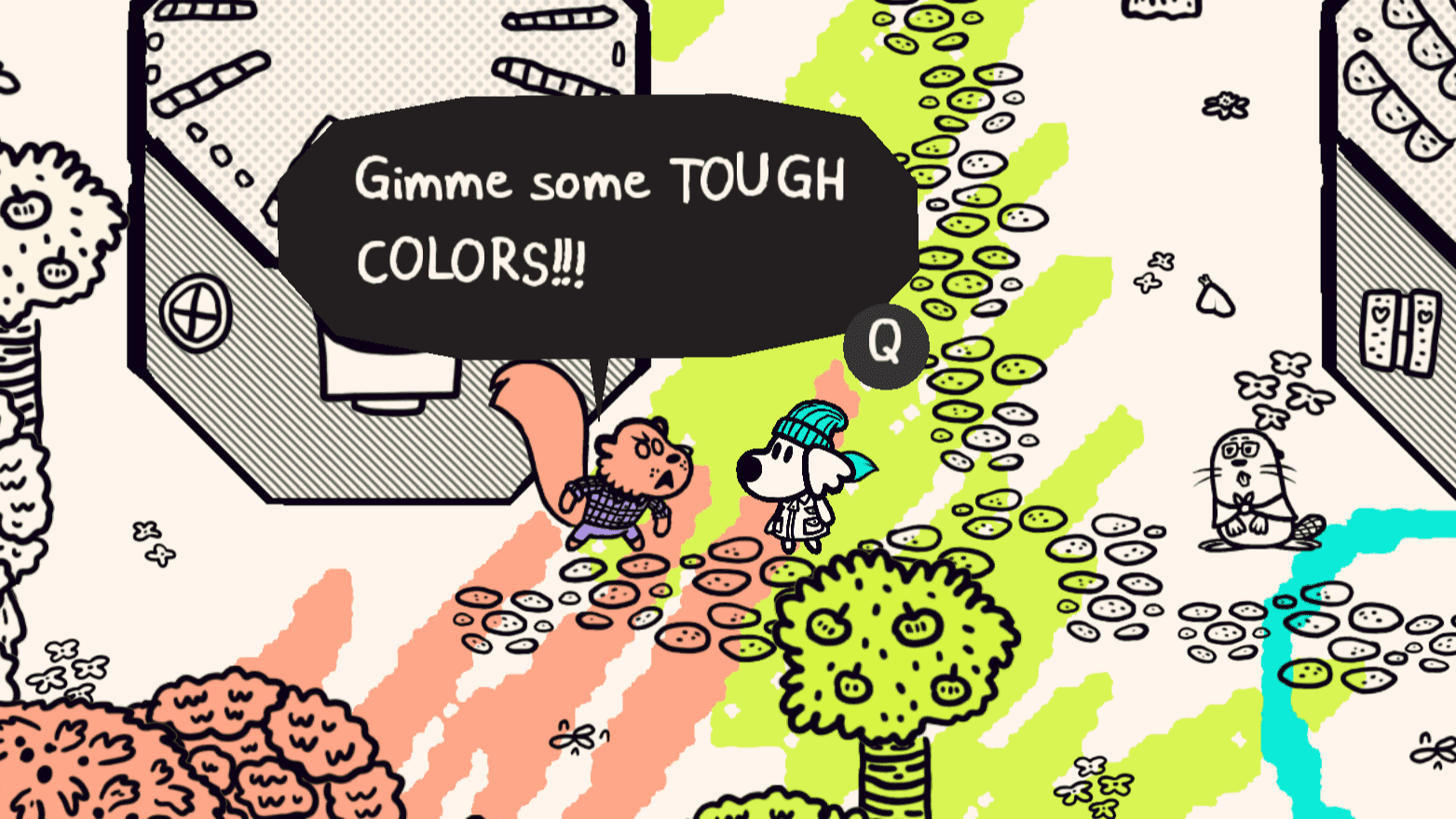

You can simply enjoy drawing and colouring in the scenery in Chicory, regardless of artistic talent.

PARENTAL ADVISORY

More recently, the choice to ‘opt out’ of challenges has been taken further in Chicory: A Colorful Tale, which combines assist options with already forgiving design. “It’s fun to make games that force the player to understand your systems,” says Greg Lobanov, Chicory’s director. “Then you watch people play your really hard game and it sucks, because they spend most of the time being really frustrated.” This realisation has led him to create games that make people feel good and take what they want from the experience. “Sometimes people just want to know what happens next in the story,” he says.

As with Celeste, the crucial factor was linking challenge to Chicory’s themes. “It’s a tool we use to create an experience,” Lobanov says, “but it’s not the reason you play the game, right?” In the case of Chicory, with story and puzzle elements, plus a focus on artistic expression, flexibility was important. “Some people are playing a Zelda game, some are playing Night in the Woods, and they’re both here,” he says. “It works for this game because it’s meant to be that.” Just as you can skip every conversation to reach the puzzles, you can equally devote your time to painting the scenery, and get help if you’re stuck.

Conquering Celeste Mountain means confronting your inner demons – literally for Madeline, with her Badeline alter ego.

You can also skip the game’s boss fights, although it took time for Lobanov to come round to the idea. He never intended the bosses to be serious roadblocks – if they knock you down, you get back up and continue without penalty – but they were carefully crafted to provide an “intense experience to feel what the character is going through”. Yet in the laid-back context of the rest of the game, some people didn’t want them at all. “It was only after two years of playtesting and hearing it from more people that I decided I really should think about this,” Lobanov says. “I was resisting the idea because I was really attached to it. I felt you would miss so much if you didn’t see your character going through conflict and struggle.”

It turned out, however, that a player’s emotional journey wasn’t drastically altered by sidestepping these hardships. “I realised that when people skip this stuff, they still get the context of it,” Lobanov explains. “Like if you’re watching a horror movie, and you close your eyes during the gory parts – it’s not like you just didn’t know that part of the story. So you’re not really missing it, in a sense.”

Chicory equally demonstrates that assistance needn’t feel like an intrusion into the narrative with one of its most memorable features – the option to phone your parents for advice. “I just really wanted your character to have a good relationship with their parents,” Lobanov says, “but they ended up playing a bigger role in the overall experience than I was anticipating.” The appeal of this feature is both that it’s available at all times within the game’s fiction, and that asking for help becomes entertaining in itself. “Because everyone uses it that one time they get stuck, it makes everyone like the game way better. I think it was a huge boost to the game.”

One problem for games like Bonfire Peaks is that they don’t fare well on Twitch. “People feel self-conscious being watched while solving puzzles,” says Corey Martin.

It was also a relatively painless addition. “I’d just have a text sheet,” Lobanov says, “and whenever I added a new screen to the game, I added two lines of text that told you how to get through it.” In cases like this, he continues, it’s the design philosophy around challenge that can make implementing assistance options either straightforward or problematic. “The fact that we did this from the beginning made it way easier,” he says. “If I had made the entire game and then at the end decided to write hints for everything, that would have been so much harder.” Considering difficulty from the start leads to a more coherently integrated whole, and it’s a practice Lobanov is keen to continue: “As I’m working on new stuff right now, I’m already thinking about how I want to make sure people get through it.”

TALES FROM THE DARK SIDE

At the same time, Lobanov emphasises that “every game’s needs are different”. For example, he says, if Chicory “was only a boss fight game, it would have been a lot harder to give you the option to skip boss fights. Why not just turn the game off at that point?” Indeed, for some games, such as Darkest Dungeon and its sequel (currently in Early Access), gruelling misfortune remains key to their identity. These roguelike dungeon crawlers could hardly contrast more with Chicory in their tone and demands, and offer no escape from their challenges. Yet their aims are effectively the same, in that both employ challenge in a way that suits the atmosphere they’re trying to convey.

“Darkest Dungeon is more about being uncompromising than being difficult for difficulty’s sake,” says Chris Bourassa, the series’ creative director. “We want to put players in an uncomfortable decision-making space, then make sure the consequences of their choices are permanent and relevant to the experiences that follow.” When the threat of loss and decline is supposed to haunt every unretractable decision, options to drastically reduce the impact of negative consequences would be an anathema.

While it has some similarities to Zelda, there’s no combat in Chicory other than the bosses.

Inevitably, this approach puts some people off, but Bourassa and design director Tyler Sigman have accepted the consequences. “Our mantra from the start was ‘This is not a game for everyone’,” Sigman says. “We make creative and mechanical decisions that we know may alienate some potential players, because we’d rather appeal super-strongly to others.” The Darkest Dungeon games need players to buy into their philosophy, and, as with many roguelikes, adapt to a different concept of ‘winning’. “Darkest Dungeon is poker, not chess,” Sigman says, “a game of imperfect information and variance that’s out of your control – but a skilled player will win more in the long run.”

With that, difficulty becomes an ongoing concern, which must be carefully curated to maintain the balance of risk-reward, even after release. “It’s a never-ending process,” Sigman says. “Balancing in this day and age where you can patch easily is live ops. Find holes and exploits, adjust, repeat.” Yet they don’t iron out all the wrinkles players might discover. “Overbalancing can result in robbing players of the rewards of their cleverness,” he adds. Nor do they tailor the game only to suit its hardcore players. “We’re already finding with Darkest Dungeon II that some players breeze through things and other players get impaled on the first challenge,” Sigman says. “You don’t want to overcorrect for the most dedicated then find you made things impossible for 95% of players.”

Bourassa and Sigman’s philosophy highlights how modern games can evolve over time. With the first game, they eventually added a new play style, ‘Radiant Mode’, which reduced the grind involved in reaching the end. “Darkest Dungeon’s mammoth campaign lagged in the middle,” says Bourassa. “We also didn’t love the average time to complete the game being anywhere from 60–80 hours – that’s a lot.” Radiant Mode isn’t easier, but it makes progress quicker, which broadens its appeal. This thinking carries across to the sequel, whose Slay the Spire-type structure makes it possible to see an ending relatively quickly without smoothing out the bumps. “We definitely wanted to explore a shorter game loop,” says Bourassa, “but we’re also excited at the spikiness we can introduce, given each run is an independent experience.”

As with the first game, Darkest Dungeon II will develop further, but will never truly compromise. “We don’t like traditional easy/normal/hard sliders,” says Sigman, “but we do like to include options that can make the game more enjoyable for different people without sacrificing what makes Darkest Dungeon unique.”

SOFT PEAKS

Constant recalibration isn’t the only way modern delivery systems can help designers deal with the problems of difficulty. Corey Martin is a purveyor of taxing puzzle games, most recently Bonfire Peaks, in which a man works his way through screens full of cunningly arranged blocks to burn his belongings. Martin is conscientious about the steepness of the challenge. “Maybe in early games I put too much of a premium on difficulty,” he says. “It’s very easy to make something very difficult, but will it be interesting at all?”

With Bonfire Peaks, Martin explains, the challenge level tended to emerge more naturally: “Ultimately, it’s about building out a system. Maybe you have some considerations of how much you want to funnel the player towards the solution, but otherwise, it’s just letting the idea decide how difficult it wants to be.” Crucially, though, he feels it should never be overwhelming. “That’s always been a turn-off for me,” Martin says, “not being able to keep all the elements of the puzzle in your head at once, and having a hard time visualising the possibilities.”

The many changes in Darkest Dungeon II include a move to 3D, adding more detail to the horror.

Still, players will inevitably snag on puzzles in Bonfire Peaks, and including traditional difficulty levels or hints wasn’t really feasible. One option would be to create a hint system offering, Martin says, “a series of less cryptic clues for each puzzle, so you can decide how far down the chain of hints you want to go”, but that would have been a big commitment. “There are a couple of hundred puzzles in the game – that’s a lot of hints,” he says, “and there’s an art to doing it cryptically, but helpfully. And then localisation.”

One tried-and-tested concept he turned to was making the game’s structure more inviting, placing puzzles in an overworld that allowed players to advance after solving only a handful of screens in each section. “If you have a linear puzzle game, like Portal,” Martin says, “where you know the player is only going to be at B because they finished A and they’re not at C yet, you have to really be careful not to challenge too much.” In Bonfire Peaks, conversely, the difficulty can be more varied. “I hope people feel encouraged to bounce around and walk away from puzzles,” Martin says. “I think having the option to try something else alleviates some of the frustration.”

If that’s not enough, you can take more radical steps, and this is where the new tech comes in, at least if you’re a PS5 owner (and PS Plus subscriber). Bonfire Peaks makes good use of the system’s activity cards, with one for every level containing a video that shows the full solution. “We shared a producer with the team from Manifold Garden,” Martin says, “and she told us how well-received the hint system was for Manifold Garden on PS5. So we thought, ‘OK, how do we offer a similar benefit?’” Having these external resources was hugely convenient. “Building out a system from scratch can be prohibitively ambitious,” Martin says. “Their system is really streamlined and it was just a matter of taking time to record the videos.”

If giving away the answers like this seems strange, ultimately it’s a measure of progress. People have always looked for help with games, from magazine guides to helplines, and there were solution videos for Bonfire Peaks on YouTube soon after launch anyway, with nothing to stop players using them. Why not make it more convenient? Tools like activity cards are yet another way for developers to mould difficulty and assistance around the kinds of experiences they want to create.

And with that, attitudes are changing. “I strongly reject any snobbery about considering any way of playing as cheating or whatever,” Martin says. “Every way of playing is valid.”

This is an edited version of a feature originally published in Wireframe #59. You can get a copy here.