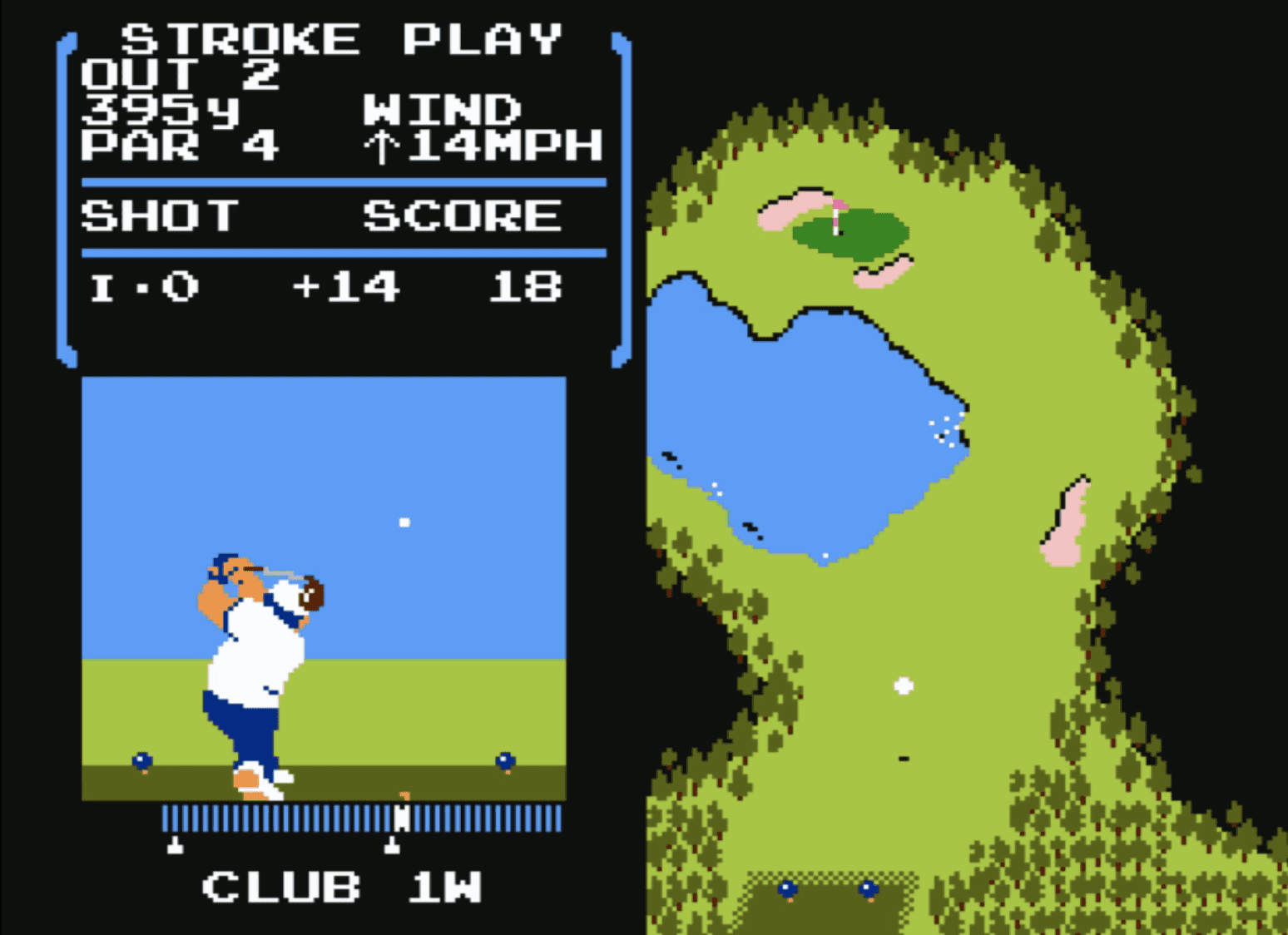

A recent column from our own Steve McNeil raised an interesting question: when did it begin? When was the first time a triple-tap system was implemented in a golf game? When was it that someone designing a game where you start your swing, peak your swing, and connect with your swing realised that could be boiled down to three button presses? Would you believe it – it was a game involving both the late, great Satoru Iwata and the great, great Shigeru Miyamoto: Golf, for the NES, first released in 1984.

Systems on a similar line did appear earlier in titles like PGA Golf for Intellivision and 3D Golf Simulation on MSX, from 1980 and 1983, respectively, but it was Nintendo’s first foray into the world of ruining perfectly good walks that the three-tap system was codified. Wireframe’s loose definition of a killer feature is something that – at the very least – made (or makes) an individual game stand out from the crowd. The fact that the triple-tap input has defined an entire subsection of sports games for 37 years now… well, that probably qualifies this as a killer feature, really.

Press one starts your swing off, with the power bar raising from zero to 100%. Press two sets the power, making a miniature game of skill in every single swing as you try to hit the exact point you need to bundle the ball into the hole. The third tap increases the skill required and shows you can’t rest until all three taps are done, as messing this one up can prove calamitous – it indicates draw or fade on a given shot, which directly links to the accuracy of the hit. The third tap is basically how true you hit the ball. And that’s it: three taps of a single button; golf turned from a dour televisual spectacle or impossible in-person task into a wonderfully straightforward, easy-to-understand game of skill and timing.

So it’s no wonder the theme has stuck ever since Golf released. Other titles came along with control schemes that danced around the three-tap method, like 1986’s Leader Board or 1990’s Links: The Challenge of Golf, both of which opted for a hold-and-release method in place of the first two button taps. Arcade titles such as Neo Turf Masters figured coin-op players weren’t quite ready for three button presses in 1996, so opted for two instead. But generally speaking, and outside of putting/crazy golf-focused titles, from the mid-eighties onwards, golf was a game of tap, tap, tap.

PGA Tour Golf, the first in EA’s now-dormant series from 1990, used the three-press method. Rory McIlroy PGA Tour, the last in the series from 2015, offered the three-press method as an option. Everybody’s Golf (1997) has used it since day one, and while it dabbled in other methods for a short time, it always came back to tap-tap-tap. Mario Golf, Camelot’s wonderful follow-on series from the original Golf game, also went for the three-tap method it invented.

Well, at least it did until Super Rush came out and opted for two taps, which rightly brought a fair bit of stick. While it makes the game more accessible, it also removes a huge chunk of your control over shots. The same can arguably be said of titles like PGA Tour 2K21 and, previously, The Golf Club, which have opted for control schemes using analogue sticks or mouse-drag-based swings.

The issue with the analogue-based schemes – and the track-ball controls seen on some arcade games of the past – is that they aren’t quite as precise as the three-tap. Inherently so, given they involve analogue input over digital. Arguments can – fairly – be made that stick/mouse/ball controls offer a more organic input method, or even a more ‘realistic’ input method than pressing a button ever could. And there’s obviously a lot of fans of pulling and pushing analogue sticks.

But it’s hard to get past that lack of real, fine control that can only come with meters and button presses. You lose the immersion and realism, true, but what you lose there you gain in the ability to really focus and play the game how you want it to be played. Unless you slip on the controller and mash the wrong button, obviously.

There’s a lot to be said for ubiquity and the need to challenge norms. It’s a good thing devs try to do something different, and there can be few arguments made in good faith that control methods like those in 2K’s golf-‘em-up don’t work. Maybe at some point, something better – something more perfect – will actually come along and everything that came before will seem so instantly quaint.

But for now, we’re still dominated by a control method innovated by Golf on the NES in 1984. Given that golf in the real world doesn’t exactly change as a spectacle at breakneck speeds, it is rather fitting that the video games imitating it don’t have to change much either. Once more for the road: tap, tap, … tap – oh crap, that’s going in the trees. FORE!

Golf-lag

One interesting way in which the old-fashioned, digital-based triple-tap does falter in the face of analogue controls – or a few of the double-tap schemes – is because of modern displays. Newer games don’t suffer this at all, of course, but older games are rendered nigh-on unplayable thanks to the usually unnoticeable display lag introduced by using modern televisions and monitors, when compared to CRTs you would have used 15-plus years ago. Everybody’s Golf on PSone, for example, is incredibly difficult because of this very sort of lag, with shot power and accuracy rarely where you want it to be without fundamentally retraining your brain for different timings. Were analogue, stick/mouse-based control schemes to be offered on older games (and they are in some, like Microsoft Golf), they wouldn’t be impacted by display lag issues, relying – as they do – more on a steady hand than timing. Ah, the fun of display lag.