Nintendo is globally recognised as the company behind hits such as Super Mario Bros., Metroid, and The Legend of Zelda. But its history goes much further back than the period in the 1980s when it first became a household name. In 1889, Japanese businessman Fusajirō Yamauchi founded Nintendo as Nintendo Koppai, a card manufacturer on Shōmen-dōri street in Kyoto. From these humble beginnings, it grew into one of Japan’s largest playing card companies, before pivoting into other products like toys and electronics.

Nintendo rarely talks at length about its pre-video game history, but it helps explain how the company came to be: from its early targeting of families with its products to why it prioritises older, cheaper hardware over cutting-edge technology. In order to find out more, we spoke to historians, collectors, and archivists about Nintendo’s growth into the company we know today. But before we do that, we first need to talk about its founder.

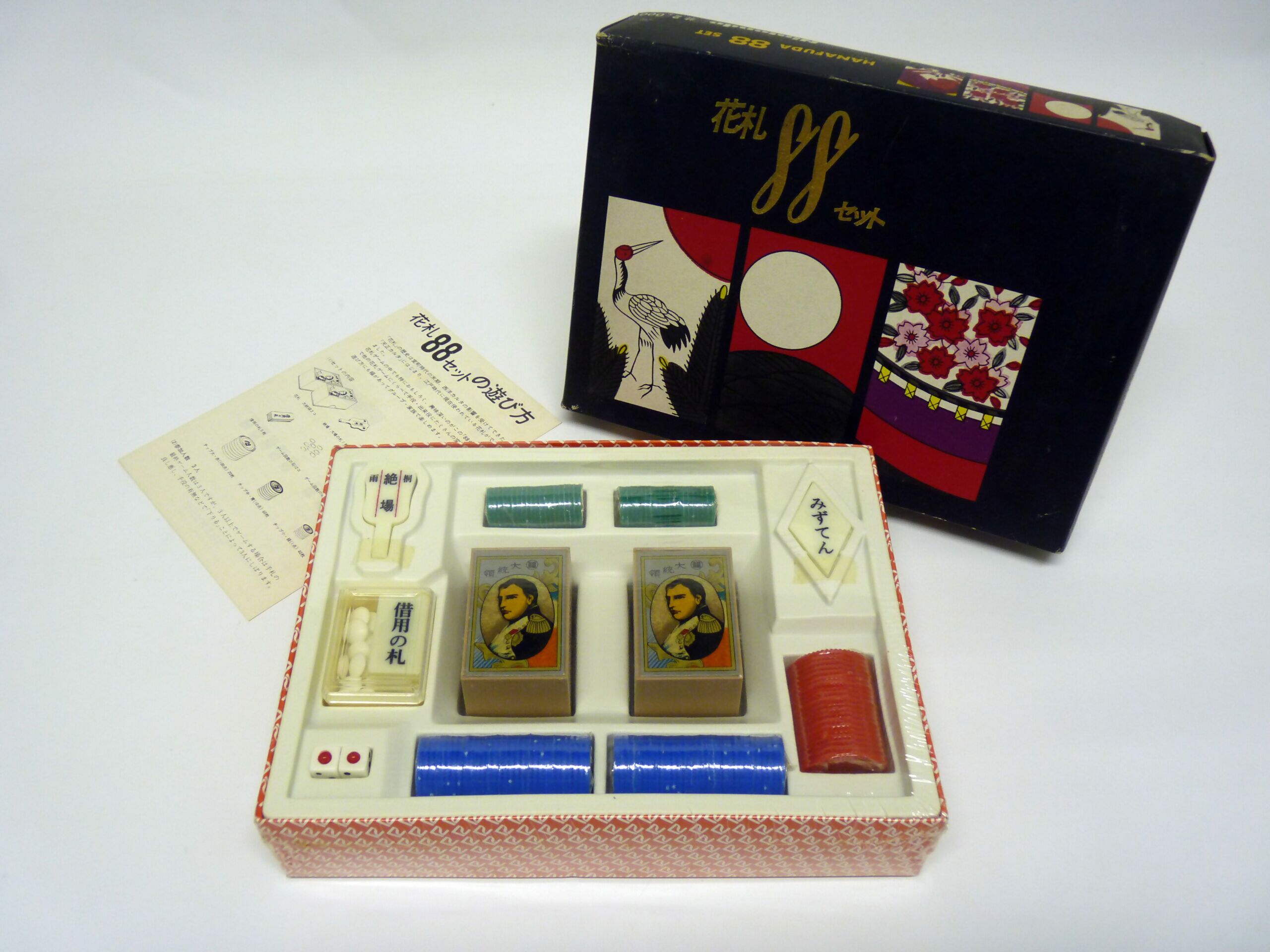

Nintendo produced various styles of playing cards over the years. Here are just a few examples. (Image: Before Mario)

CEMENT TO PLAYING CARDS

Fusajirō Yamauchi wasn’t born a Yamauchi, but was instead adopted at an early age. Naoshichi Yamauchi, the owner of the local cement company Haiko Honten, had no children and needed an heir to take over after he retired, so Naoshichi adopted Fusajirō and changed his surname. Fusajirō started working at the factory as a teenager, and in 1880 succeeded Naoshichi as president, becoming involved with projects like the Lake Biwa Canal in Kyoto. The company’s success continued under his leadership, but Fusajirō had other interests he wanted to pursue outside of cement.

In his spare time, Fusajirō often played with Hanafuda. These were pictorial ‘flower cards’ containing twelve suits, each one representing a different month, and encompassing four ranks. In the past, playing cards had been outlawed under the Tokugawa Shogunate, but were legalised again in 1885 after the Meiji government softened its position on gambling.

Florent Gorges, co-author of The History of Nintendo 1889–1980, says: “Around [1885], Japan started to change its philosophy, its ways of life, and the government again allowed the possibility to gamble with cards. Mr Yamauchi loved to drink saké with his friends after work and to gamble with playing cards for money. And because [Kyoto] was considered a pleasure city, he asked himself, ‘Why can’t we do a card-manufacturing business?’”

“There was a new opportunity,” adds Alexander Smith, author of They Create Worlds, a book about the key figures behind the video game industry. “Hanafuda had just been legalised again, so there really weren’t that many manufacturers. There was an opportunity to start a small workshop, and that’s how Nintendo started – just a side business in 1889 in a small building, with maybe only a dozen artisans hand-crafting these Hanafuda cards.”

Nintendo produced Disneyfied takes on traditional games like Iroha Karuta, but also western-style playing cards for kids. (Image: Before Mario)

Nintendo’s first Hanafuda set, the Daitōryō (“president”) line, featured the image of Napoleon Bonaparte on the cover and was aimed at the higher end of the market, such as gambling houses and those with more expendable income. Nintendo later released another deck called the Tengu line – comprising cards of a slightly lower quality.

The Tengu (literally “Heavenly Dog” or “Heavenly Sentinel”) is a legendary figure in Japanese folklore, commonly depicted with a long nose and a red face. They were already associated with gambling, because the Japanese words for “nose” (hana) and “flower” (hana) have a similar pronunciation, and potential players would often rub their nose to indicate that they were looking for gambling games during prohibition.

For years, it had been assumed that the name Nintendo means “Leave Luck to Heaven”, but Hiroshi Yamauchi has admitted in interviews that its true meaning has been lost to time. Gorges therefore speculates that because of the cultural connection between the Tengu and gambling, and due to the ten in Nintendo using the same kanji as in Tengu, it’s possible the company was partially named after the figure instead.

MODERNISATION

The success of Nintendo’s products resulted in continued growth over the next two decades, but that success also brought with it some challenges. During the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the Japanese government imposed a stamp tax on playing cards – a system that continued to exist up until 1989 (before being replaced with another tax similar to VAT). This change hit some card companies hard, but Nintendo managed to weather these changes due to its various partnerships and growing catalogue of playing cards.

Having grown Nintendo from a small side business into a profitable venture in its own right, Fusajirō retired in 1929. He selected Sekiryo Yamauchi, the husband of his daughter, Tei, to take over from him, and immediately Sekiryo modernised Nintendo. He introduced a new management structure and introduced production lines. But difficult times were ahead.

Hyakunin Isshu (or Uta-garuta) is a matching game based on a classical anthology of Japanese poems. (Image: Fabrice Heilig)

In 1941, Japan entered World War II and the public’s interest in leisure activities fell dramatically. To survive, Nintendo took a contract from the Japanese nationalist government to produce Aikoku Hyakunin Isshu (a patriotic take on the popular poetry game). It’s a controversial part of the company’s history which Nintendo has never discussed. “During wartime, you can’t really be a leisure company,” says Kelsey Lewin, co-director of the Video Game History Foundation. “So they managed to stick around by being a propaganda company for the Japanese nationalists. They made cards with nationalist slogans on them which were distributed to soldiers.”

“Nintendo printed them and shared them all around Japan,” says Gorges. “And they had orders from all the schools. For Nintendo, it was a great opportunity for them to survive, because nobody was in the mood to play games. All the men were at war. The women were all working. And the kids were at school. So the entertainment industry in Japan was in a bad situation.”

This wasn’t necessarily unique to the Japanese wartime experience, with some American companies like Disney also having to survive through signing contracts with their nation’s armed forces. Nevertheless, Nintendo emerged from the war because of this work, and like other Japanese companies, it began to rebuild. Sekiryo established another business called Marufuku Co. Ltd in 1947, to help with distribution of Nintendo products. But, in 1949, he suffered a stroke and ceded control of the company to his grandson, Hiroshi.

Hiroshi Yamauchi wasn’t the first choice to take over as president of Nintendo, as he was still quite young at the time. Instead, Shikanojo Inaba, Hiroshi’s father and Sekiryo’s son-in-law, was first in line to succeed. But Shikanojo had abandoned his family and fled from his responsibilities, so Hiroshi became president at only 22 years of age.

STRIKES, DISNEY, AND TOYS

Hiroshi took a draconian approach to management, bringing about a number of dramatic changes that frustrated long-time employees. In 1951, he consolidated the family’s corporate entities and centralised production, leading to a number of factory closures and layoffs. Employees voiced their disappointment with the young president and organised a protest in 1955, with many workers expecting him to fold under the pressure. But Hiroshi instead laid off his biggest critics, forcing employees to fall in line or face punishment.

For the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Nintendo released a deck of cards featuring Mickey and friends. These underperformed, however, as Japanese children shifted their attention from playing cards to plastic toys. (Image: Fabrice Heilig)

The next year, Hiroshi visited the world’s largest card manufacturer: the United States Playing Card Company, in Cincinnati. It was on this visit that Hiroshi realised that Nintendo would need to diversify its business in order to survive. “When he visited the United States, it was to get a sense of what the card business looked like there,” says Smith. “And it was kind of a revelation to him that children were playing cards. Because it just wasn’t [common] in Japan. And this was one of the reasons why he shifted focus [to children]. It’s also kind of when he learned the power of licensing.”

Gorges says: “When Mr. Yamauchi went to the US, he wasn’t impressed when he discovered that the world’s biggest playing card company wasn’t so different to Nintendo at that time. He was disappointed because he had such great ambition, and didn’t see any great future for his business.”

In 1959, Hiroshi began diversifying Nintendo, signing a licensing deal with Disney to make cards based on its animated characters. This new range was an instant hit with Japanese kids, and Hiroshi took the company public soon after in 1962.

A year later, Hiroshi changed the company’s name to Nintendo co., dropping the reference to playing cards for the first time. Plastic toys were becoming increasingly popular with Japanese children, and with the playing card market plummeting in 1964, Nintendo needed to expand into other areas.

From 1965 onwards, Nintendo produced a variety of board games based on characters from Disney films and Japanese media; and existing products by Milton Bradley and the Parker Brothers. At this stage, the company was yet to develop its own original ideas, but all that was about to change with the arrival of one young engineer, Gunpei Yokoi, in 1965.

Yokoi initially maintained the card-cutting machinery on Nintendo’s factory floor. He liked to tinker, and during his shifts would often build contraptions out of materials he found around the factory. The story goes that, one day, Yokoi was bored and tinkering with an extendible-hand toy he’d built, when management took notice and brought him up to the office. Yokoi thought he was about to be punished, but Yamauchi instead promoted Yokoi to an R&D position and asked him to produce more. Nintendo released the toy as the Ultra Hand in 1966 to commercial success, giving the company a new-found confidence.

The Nintendo Beam Gun was produced in collaboration with Sharp’s Masayuki Uemura. Uemura later joined Nintendo and designed the original Famicom. (Image: Fabrice Heilig)

GAME & WATCH

Yokoi’s emphasis was on creating cheaper products using technology that was easy to source and manufacture. In 1967 came Yokoi’s next invention, a plastic batting toy called the Ultra Machine, followed by Nintendo’s own take on LEGO called N&B Blocks. Nintendo also started to produce electronic products around this time, including a Love Tester, a light-sensitive Beam Gun, and a remote-control car called the Nintendo Lefty RX. “There’s this Yokoi philosophy that extends into Nintendo even now,” says Lewin. “He called it ‘lateral thinking with withered technology’. What that means is taking parts that are cheaper now, off-the-shelf and not cutting edge, and making something really good and interesting with them. That way you can have something that’s affordable, but not sacrifice quality too much.”

Nintendo had some initial successes with this philosophy, and some notable failures, too. One such failure was the Laser Clay system in 1973 – Yokoi’s idea to transform the nation’s deserted bowling alleys into toy shooting galleries. Together with fellow R&D members Masayuki Uemura and Genyo Takeda, Yokoi came up with a kit that used projectors to simulate a shooting gallery. When a person fired their gun, mirrors would track the light and detect whether the target was hit, switching the projector image based on this input. The attraction was initially popular, but the Japanese oil crisis and recession led investors and business partners to pull out, causing Nintendo to lose millions.

The company was in trouble; one of its biggest projects had fallen apart, and toys were becoming more expensive to produce due to the rising costs of manufacturing. Nintendo again needed to pivot to survive – and luckily, coin-operated amusements were on hand.

The Game & Watch had over 50 variations, including several multi-screen handhelds. (Image: Before Mario)

In 1974, Nintendo released a mini version of its laser-clay shooting system: the arcade machine, Wild Gunman. It was a modest hit, and Nintendo followed this with other coin-operated amusements like Genyo Takeda’s EVR Race and Sky Hawk. The company started to prioritise video games over toys, and in the late 1970s, after the success of Atari’s home version of Pong, Nintendo acquired a licence from Magnavox (Pong’s original creators) to create its clone consoles for the home market.

Together with Mitsubishi Electronics, Nintendo released the Color TV-Game 6 and Color TV-Game 15 – home consoles packaged with variations on Pong. Other systems followed, including the Racing 112, a driving game, and Block Kuzushi, a clone of Atari’s Breakout. Despite these consoles selling particularly well, the company wasn’t in the clear. In 1980, however, its fortunes started to change.

As Yokoi was riding home on the bullet train one day, he spotted a bored businessman playing with the buttons on his calculator. This gave him an idea, and pretty soon he came up with a proposal for a portable LCD gaming device, using button-cell batteries which were cheaper to source. He called it the Game & Watch, and it would go on to become the hit the company needed. Nintendo released the first version of the Game & Watch in 1980, and over the next few years, it created more variations with various different games included, like Life Boat, Rain Shower, and Mario Bros.

Following this, the story of Nintendo becomes more familiar. In the early 1980s, it released arcade cabinets for Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. It then followed this in 1983 with the release of the Family Computer (or Famicom), a console designed by Masayuki Uemura. With each subsequent release, Nintendo built a reputation for quality and innovation through “lateral thinking” – skills that came about from raw talent and financial necessity.

Today, Nintendo only really acknowledges its pre-video game history in the form of easy-to-miss Easter eggs. But if you look closer, its influence can be seen in many of its products, whether it’s the Wii, Wii U, and Switch, or peripherals like Labo and Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit. The company rarely tries to dominate its rivals with superior technology, instead offering affordable experiences that appeal to a broad audience. It’s an approach that has served the company well for years, and one that it will likely continue far into the future.