This article first appeard in Wireframe issue #5. It’s now republished here in honour of Tunic’s recent launch on Xbox and PC.

Keeping secrets isn’t easy these days. Thanks to the internet, leaked details of a major franchise sequel can spread around the world within seconds. Videos of a game’s ending can appear on YouTube or Twitch within hours of release. For now, though, isometric adventure Tunic has an enticing air of mystery surrounding it. Its lush world is full of ancient ruins and hidden pathways; in-game text is written in an unintelligible script, not unlike the exotic language of Fumito Ueda’s classic, Ico; even the identity of its protagonist, a plucky fox in a green tunic, is currently unclear.

Like its fox, who boldly lopes into battle with his tail

bobbing along behind him, Tunic can maintain its sense of mystery

because it’s so small. For the past four years, Canadian developer Andrew

Shouldice has been working on the game largely by himself, with occasional

YouTube dev diaries and Twitter updates offering only tantalising glimpses of

his work in progress. Indeed, the sense of mystery is something that has formed

a core of Tunic from its inception.

“The concept of the game was really an old idea that’s been

in my head for a long time,” Shouldice tells us. “But the more I think about

it, the more I realise what a vague idea it was. It was this feeling – this

type of experience, where you feel like you’re a stranger in a strange land.

You’re entering a place where you don’t belong. As this vague idea turns into

an actual game, we’re still managing to hit that feeling of a sprawling,

unknowable world with a bunch of strange rules.”

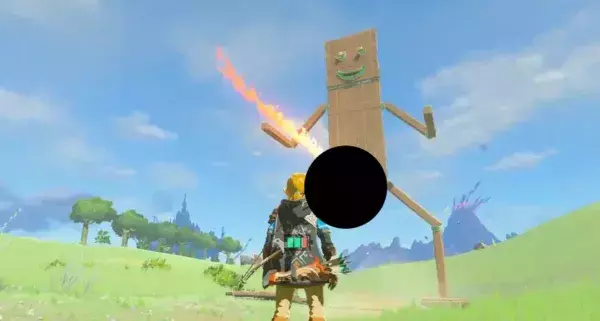

It’s a description that vaguely recalls Shigeru Miyamoto’s

now legendary inspiration for The Legend of Zelda, in which he attempted to

capture the sensation of exploring the Kyoto countryside as a child. And, as

you’ve probably noticed, Tunic has more than a touch of Zelda about it;

the fox, with his sword and shield, is a hero firmly in the mould of Link while

the lock-on combat system handles similarly to the one in Ocarina of Time.

TREASURE HUNT

But while Tunic might positively invite comparisons

to Zelda, it has its own twists on the Miyamoto formula, from the isometric

perspective to an overarching air of self-awareness that reminds us a little of

Fez. Just as Phil Fish’s indie masterpiece constantly reminded us of the

artificiality of its sumptuous 2D world, so Tunic throws in little

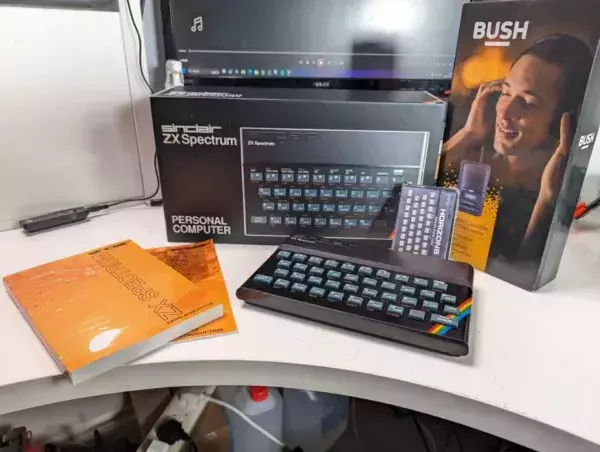

postmodern ideas. Open up a treasure chest, and you’ll occasionally uncover a

page torn from a video game manual – a manual written for Tunic itself.

“One of the things I want people to have is the feeling of

sitting down and playing a video game that you don’t understand the boundaries

of,” Shouldice explains. “I think of myself playing a video game aged five,

leafing through the manual, not understanding any of it, bumbling around and

not really understanding what the rules of video games are, let alone what the

rules of this video game are. Part of that, I think, is having text that feels

like it’s not made for you.”

Appropriately, Tunic has been a journey of discovery

for Shouldice himself. Back in 2014, he quit his job as a developer at Nova

Scotia’s Silverback Productions to work on the game, then called Secret Legend.

Armed with a degree in computer science and experience of shipping games,

Shouldice already had plenty of skills to fall back on, but going indie has

nevertheless presented a number of challenges – including a crash course in 3D

animation.

“I did a lot of 2D animation in my old job, just sliding

stuff around,” Shouldice says. “I remember the first time I used Unity’s

animation system, and I tried to make a ball bounce, and I was like, ‘This is

awful. This is terrible. Burn it! I’m never doing this again.’ And then of

course I got used to it. So really, it’s been over the course of this project

that I’ve learned how to do more 3D modelling and animation.”

Cannily, Shouldice designed Tunic’s world around his

own limitations: he found ways of constructing assets like bushes and tufts of

grass from as few vertices as he could, resulting in the low-poly style that

makes Tunic so eye-catching.

“I wanted to keep everything simple originally, not being

especially good at doing modelling and animation,” Shouldice says. “I charted

out where vertices should go on graph paper, because that was easier for me to

conceptualise what the character should look like. Trying to do it with as few

vertices as possible so I didn’t have that much geometry to deal with.”

Rather than wrestle with high-poly character models,

Shouldice has instead focused on getting little animated details just right –

the tactile way the grass bends as the player moves through it; the puff of red

hair that bounces on the fox’s head as he runs.

“One of my favourite things to do is just go in and add

polish – little, tiny things that might be a fraction of a second, but you see

them a lot. I feel like that’s the maximum pay-off – I can tweak some curves

just here, and then all of a sudden, every time the player moves around, they see

this little bounce. That’s a good cost-value trade-off sort of thing.”

Lighting is another detail that adds atmosphere and depth to

Shouldice’s low-poly world: flecks of light shimmer along the ground in a

woodland, suggesting a canopy of trees above, while on the beach, grey cliffs

are bathed in diffuse sunshine.

“Very early on, I knew I wanted to have this soft light,

where if a surface is strongly illuminated, the object itself isn’t just

bright, but other walls near it are bright,” Shouldice says. “Like when

sunshine falls on a hardwood floor, the room is filled with this light golden

glow. It’s really pleasant and makes the whole place feel bright and shiny.

Then when you go through a forest, that feel is characterised for me by that

dappled light on the floor. It’s trying to get to the core of, ‘what can I do

to communicate a feeling [without] a team of artists working on it?’ How can I

deliver that emotional payload with an abstracted representation of these

things?”

Not that Shouldice has attempted to tackle everything in Tunic’s

development himself. For sound design, he turned to Power Up Audio, the

Vancouver-based team who recently won an award for Celeste; musician Terence

Lee – also known as Lifeformed – is behind the ambient soundtrack. He’s also found

a valuable ally in Finji, the developer and publisher that distributed such

games as Night in the Woods and the forthcoming Overland.

DISCOVERY

“It was just this natural collaboration that turned into

something more official as we got to know one another,” Shouldice says. “If

this game is going to have a publisher, then Finji is going to be publishing it

– it just makes sense. That’s when I met Harris [Foster, Finji’s community

manager], who is helping out with all kinds of stuff, like running shows and

setting up interviews and managing our community.”

It’s a partnership that quickly bore fruit; in June 2018, Tunic

was one of the games prominently displayed in Microsoft’s E3 Indie showcase.

Now a console exclusive for Xbox One, Shouldice’s little adventure game has a

wider potential audience than ever.

Says Shouldice, “It’s the sort of trajectory that, if you’d

told me this five years ago, I’d be like, ‘That’s the dream, isn’t it?’ Ha.

Anyway… I started posting Vines – RIP Vine – on Twitter a few months after

development started, and people just picked up on it and got enthusiastic. It

fuels me to this day, really, that there are actually people who are excited

about this.”

Despite the growing anticipation surrounding Tunic,

Shouldice remains intent on retaining his game’s air of mystery. He draws the

distinction between the feeling of solving a clue in a point-and-click

adventure and that of stumbling on a hidden secret that was never really meant

to be found.

“It’s the satisfaction you get when you get to the end of a

chapter in a book and there’s a big cliffhanger or the murderer is revealed, “Shouldice

says. “That’s cool, but on the other end of the spectrum, there’s something

that you actually discovered: a new fact about the world that was deeply

hidden. It’s like reading that mystery novel and being like, ‘That was good’,

and then realising that if you take a razor blade and cut the page down the

middle, there’s a secret page in between there that has something more on it.

It feels like you really weren’t meant to find it.”

WORLD BUILDING

Creating those hidden mysteries, however, takes time. While Tunic’s

core is pretty much done, Shouldice still has several months – perhaps a year

or more – of development before the game is finished.

“One of the things I’ve learned is [that] building content

takes a long time,” Shouldice tells us. “The feel of a game, the mechanics –

you can fine-tune and polish those a lot. But giving the player something to do

that is compelling, and hand-crafted, and feels new, takes a lot of time; going

back and trashing stuff and reiterating and redoing it. There’s no specified

release date at this point, but that’s the thing that I’ve been spending a lot

of time doing – basically building new areas for the player to explore.”

The question remains, though, whether Tunic will be

able to keep its aura, especially once it’s released and all those content

creators start creating their YouTube and Twitch videos. “Perhaps it’s inspirational,”

Shouldice admits. “I don’t know if people are going to come away with that feeling,

but I desperately hope that it’s the case.”

Finji’s Harries Foster, on the other hand, seems confident

that we’ll be talking about Tunic’s secrets for some time to come.

“It has a feeling of mystery that I haven’t felt in 15

years.” Foster enthuses. “We have the internet now, which makes these things

way easier, but Tunic makes you want to get out there and talk to your

friends about it. I think it’s a game people will want to scratch their heads

over, out loud, with other people.”