Japanese firm SNK has taken on many guises – and several variations on its name – since its founding in 1979. But while SNK’s video game output has spanned genres from sports titles to puzzles to military shooters like Metal Slug, the company’s arguably best known for its array of competitive fighting games. From 1991’s Fatal Fury: King of Fighters onwards, SNK blazed a trail with some of the tightest, most vibrant fighters ever made.

For these, we partly have Takashi Nishiyama to thank – one of the key figures working at SNK in the early nineties, and a developer who’d helped transform the fighting genre in the previous decade. At Irem, Nishiyama created the groundbreaking brawler, Kung-Fu Master, in 1984; moving over to Capcom, he revolutionised one-on-one combat with the original Street Fighter – the game that first introduced the idea of a six-button layout for punches, kicks, and combos.

Having been hunted by SNK shortly after Street Fighter’s release in 1987, Nishiyama soon had another revolutionary idea: cartridge-based arcade hardware. “Until [the early nineties], arcade operators would have to purchase a machine for each game,” Nishiyama explained in a rare 2011 interview with 1up.com. “By creating a hardware system with cheap software, we were able to sell a lot of games even in pirate-heavy markets, and I think that was one of the main factors that led to SNK’s success.”

Samurai Shodown (also known as Samurai Spirits) added weapons to the one-on-one fighter mix.

The result was the Neo Geo: a system that brought cutting-edge gaming hardware to both arcade owners and – if they could afford it – gamers at home. The first wave of games developed for the Neo Geo had military and sports themes (NAM-1975, Baseball Stars Professional, Top Player’s Golf), but Nishiyama still had unfinished business in the fighting genre, and soon brought his expertise to bear on SNK’s first one-on-one brawler for the Neo Geo, Fatal Fury: King of Fighters.

That game not only introduced a number of familiar characters that would continue to pop up in both Fatal Fury sequels and elsewhere – Terry Bogard and villain Geese Howard, to name but two – but also SNK’s approach to the fighting genre. There were the bold character designs and fluid animation; the taut combat, which required precise timing to master; and its two-lane battle arena, which allowed opponents to move between the foreground and the background to evade attacks.

ROUND ONE

From there, SNK’s roster of fighting games ballooned as the broader company’s success grew through the early nineties. As head of development, Nishiyama personally oversaw the likes of The King of Fighters and Samurai Shodown, while Hiroshi Matsumoto created Art of Fighting, released in 1992 – all games that received multiple sequels as the decade wore on.

Series debut The King Of Fighters ’94 served as a crossover between multiple SNK properties, with characters from its earlier titles making an appearance.

“Working at SNK in the nineties was so surreal,” recalls Naoto Abe, an artist and character designer who worked on such games as Metal Slug, The King Of Fighters XIV, and 2019’s Samurai Shodown. “The Neo Geo first went on sale in 1990, and SNK was blessed with multiple hit fighting games. You could feel the company growing in your bones. More were added to the development line, and each dev team really fed into and received a ton of positive stimulation.”

Yasuyuki Oda, producer of such series as The King of Fighters, Fatal Fury, and Art of Fighting, joined SNK in 1993 at the age of 20, and remembers the excitement and camaraderie at the time, with teams sectioned off and working on their own separate projects. “If you had talent and drive, you could take on really crucial work,” Oda says. “The developers back then were all young – I’m pretty sure the oldest was in their early thirties. There was always this pressure to make something better than the other teams, but it never came down to rivalry. We got along really well.”

Nobuyuki Kuroki – who joined SNK around the same time as Oda and most recently served as project supervisor on The King Of Fighters XV – recalls that teams commonly comprised around 10–15 people. The pace of work was fast, and, he remembers, the hours were sometimes brutally long. “When I joined, SNK was deep in development of Fatal Fury Special,” Kuroki tells us, “so it was literally the busiest time for us ever. Us newbies were debugging 24 hours a day on alternating shifts. It was a gruelling process, but as Fatal Fury Special was a really fun game, and I got along well with my co-workers, I actually enjoyed myself quite a bit. Also, I joined SNK because I was a big fan of Art of Fighting, so you can imagine how excited I was to hear that they were developing Art Of Fighting 2 right next to my office.”

RIVAL SCHOOLS

SNK’s clear rival in the fighting genre stakes was, of course, Capcom. And while Street Fighter 2 and its updates were the clear winner in terms of global attention, SNK continued to carve out its own niche with fighting games that concentrated on varied combat techniques, timing of special moves, and neat additional flourishes like dedicated taunt buttons.

Six artists spent 18 months drawing Metal Slug’s stunning sprites, according to Naoto Abe.

Like Nishiyama, Yasuyuki Oda is another developer who’s worked for both Capcom and SNK. So we had to ask: does he think there’s a fundamental difference in how the two studios designed their fighting games?

“SNK was heavily concerned with fighting game balance and difficulty against CPU opponents due to their focus on arcades,” Oda says. “I feel like SNK focused more on CPU fights than Capcom because they had cabinets not just in large arcades, but also smaller shops that could only had a limited amount of space.”

By the middle of the 1990s, Midway had turned heads with its Mortal Kombat series, which used digitised graphics for its characters, while Sega had seen huge success with Virtual Fighter: a 1994 coin-op that successfully fused traditional 2D combat with 3D character models. Behind the scenes, SNK was also trying to move with the times, and exploring the possibility of using 3D models and motion capture in the early development of 1996’s Art of Fighting 3: The Path of the Warrior. “Back then, SNK internally was still researching 3D technology,” says Nobuyuki Kuroki. “There were huge expectations because the thought was if you used motion capture, then you can make a really amazing game. Two of our staff members went to America for about a month to record some motion capture for the game.”

Ultimately, this approach proved to be a creative dead end, though the motion capture data was still used indirectly to help the team understand “how the body looks during specific moves” as they drew the game’s 2D sprites.

Although widely regarded as a difficult series for newcomers, producer Yasuyuki Oda argues that King Of Fighters XV “has found a good balance, and new players have joined because of it.”

DECLINE

Inevitably, the nineties hunger for competitive fighting games wouldn’t last forever, and SNK’s fortunes began to take a downward turn as the new millennium beckoned. Ventures like the Neo Geo CD or the Neo Geo Pocket handheld (see box, overleaf) failed to gain much traction, and SNK filed for bankruptcy in 2001. Franchises like The King Of Fighters continued to see updates through the 2000s, but these were developed by companies like BrezzaSoft and Playmore, founded by former executives at SNK.

In ownership terms, the next 15 years were a turbulent time for SNK; briefly owned by pachinko manufacturer Aruze, the brand was acquired by Playmore in 2003. The resulting company, SNK Playmore, made another attempt to return to the console market in 2012 with the Neo Geo X, a poorly received handheld console that ceased production just one year after launch. But while SNK has had its share of ups and downs in recent years, it’s weathered the storm where other companies of its vintage have withered and died. Now partly owned by, of all people, Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman, SNK’s still putting out games and even the odd bit of hardware: the NeoGeo Mini nostalgia device emerged in 2018, while this year saw the release of The King of Fighters XV.

CHANGING TIMES

SNK experimented with motion capture and 3D models for Art of Fighting 3, but ultimately stuck to the traditional hand-drawn sprites.

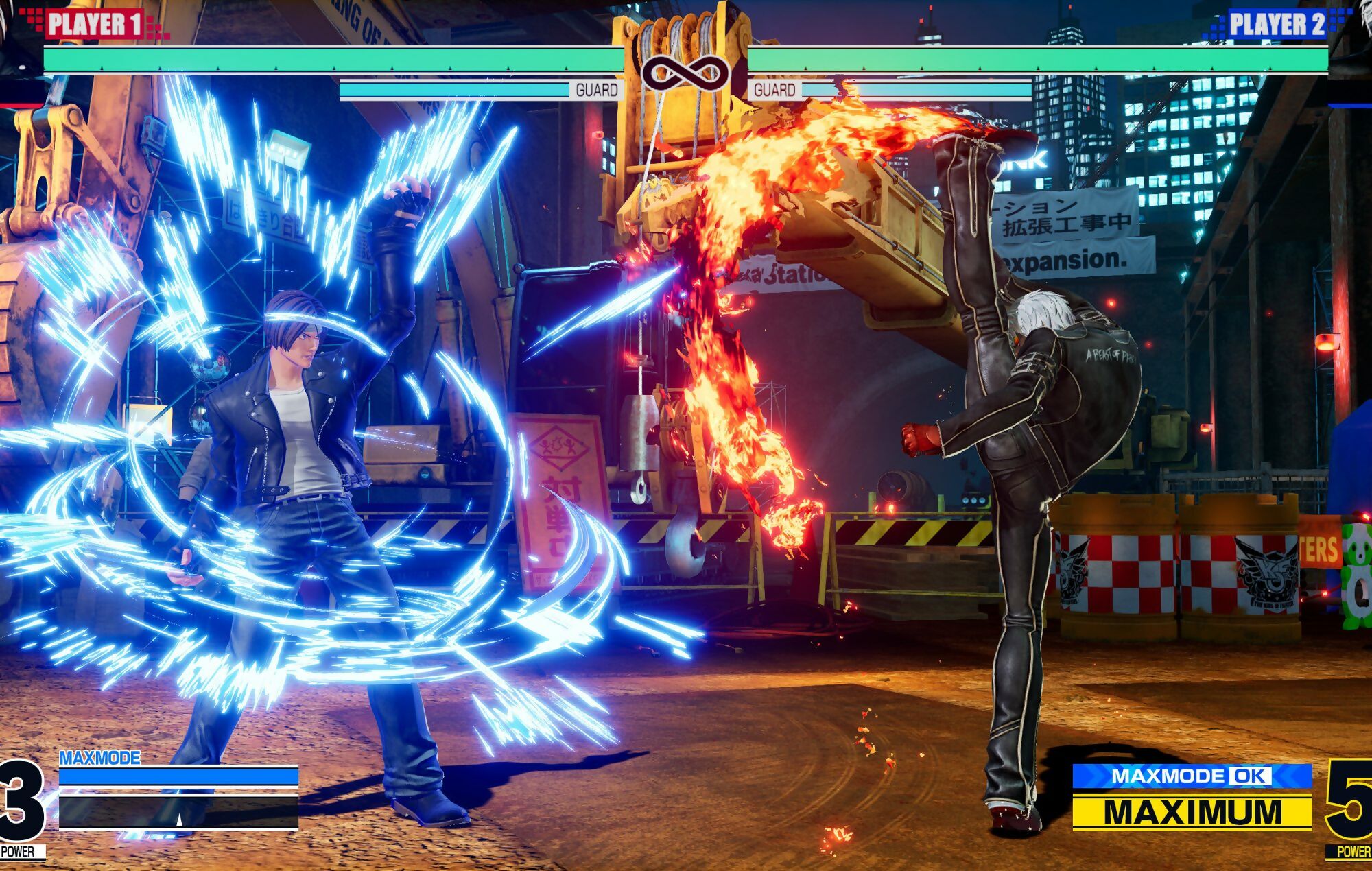

Today, SNK’s developers are still evolving and experimenting with each game they make. King of Fighters XII and XIII used 3D models as a basis for their hand-drawn sprites, before the series finally made the leap to full polygonal 3D models with King of Fighters XIV. Although the move to 3D assets saved on development costs – hand-drawing every frame of those enormous fighters takes time, after all – the transition wasn’t without its challenges. “The way of animating 2D patterns and 3D keyframes is completely different, so recreating it is incredibly difficult,” says franchise stalwart and King Of Fighters XV creative director, Eisuke Ogura. “On the other hand, characters like Ramon benefited greatly from the move to 3D as his movement is rich and fluid. Another advantage is being able to use the dynamic camera.”

King Of Fighters XV also brings with it another technical change: a shift from a proprietary engine to Unreal Engine 4. “With the introduction of UE4,” Ogura explains, “we were able to add depth of field and better shaders, which really give the overall presentation a real kick. We even use it to brush up the models to make them look more lively.”

“I can’t even imagine not using Unreal Engine 4 at this point,” concurs project supervisor Nobuyuki Kuroki. “It’s come in really handy.”

Another challenge both Ogura and Kuroki point to, on King of Fighters XV’s development, was the style of those 3D visuals. “Even though we’re using UE4 and a lot of things have become easier, one thing that took a ton of time was hammering down an art style that we liked,” Ogura tells us.

For 2019’s Samurai Shodown, SNK initially toyed with a more photoreal look, before opting for the ‘anime’ style seen in the finished release.

“We had a hard time deciding on an art style we were satisfied with,” Kuroki agrees. “The same thing happened with [2019’s] Samurai Shodown. It started off as being photorealistic, and then we tried other styles, eventually making it more ‘anime’-looking. It was tough to get it looking like King of Fighters. In the end, we went with an art style that can be appreciated at a glance, instead of something that was an acquired taste, and I’m glad we did.”

Indeed, The King Of Fighters XV’s visuals were widely singled out for praise when it launched in February 2022, and the game as a whole is generally regarded as a worthy addition to the long-running series.

As for SNK today – well, the firm may be very different, but more than a hint of that same creative spirit still remains. “The company, staff, and how the games are made have all greatly changed,” says Naoto Abe. “But, including myself, there are still people in the company from the Neo Geo days. They’re all in major roles in the company making games, and so you could say the spirit of SNK hasn’t changed. It’s still being passed on.”