The King’s Quest franchise owes its existence – in a roundabout way – to the teletype. In the late seventies, contract programmer Ken Williams brought one of these devices – essentially a printer which could send and receive messages – home with him from work. Keen to find the Star Trek game that had inspired his love of computing, Ken and his wife Roberta stumbled on a different title: Will Crowther’s Colossal Cave Adventure.

It was this pioneering text adventure that inspired the husband and wife duo to develop their own games, a dream they soon realised with Mystery House – the very first graphical adventure – as well as the formation of their own software company, On-Line Systems, later rebranded Sierra On-Line.

The company released many groundbreaking adventure games over the next 20 years, including Space Quest, Quest for Glory, and Phantasmagoria. It was the King’s Quest series, however, that was most closely associated with Sierra On-Line’s fortunes: from the original King’s Quest, which was an early hit in 1984, to 1998’s King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity, which saw the end of the Williams’ involvement with the studio.

Sierra On-Line’s co-founders Ken and Roberta Williams now spend most of their time travelling the world on their own adventures.

The couple no longer do many interviews about that era, and spend much of their time travelling the world on their boat, but we spoke to them recently, as well as other notable Sierra On-Line alumni, about the history of the King’s Quest series, and its lasting legacy.

Wizard and the Princess

To tell the story of King’s Quest, you first have to tell the story of 1980’s Wizard and the Princess – a precursor of sorts to the King’s Quest series. Taking place in the land of Serenia, it tasked players with rescuing King George’s daughter Princess Priscilla from an evil wizard.

The game was played using a parser system, a textbox which allowed users to type their commands directly into the computer. It was an important title for Sierra On-Line, not least because it was the company’s first colour game, employing the use of dithering to create the illusion of a larger colour palette.

2_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

2_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />Sierra’s games were dazzlingly colourful for the time.

As a result, the game caught the attention of IBM, who not only licensed it for its computers under the title Adventure in Serenia, but also asked for an enhanced version for its upcoming IBM PCjr machine.

“Roberta started developing this version of the game, but, as Ken recalls, “She wanted to add animation.” So, instead of just doing a straightforward port, Roberta began developing a whole new title, which would become King’s Quest.”

Arise, Sir Graham

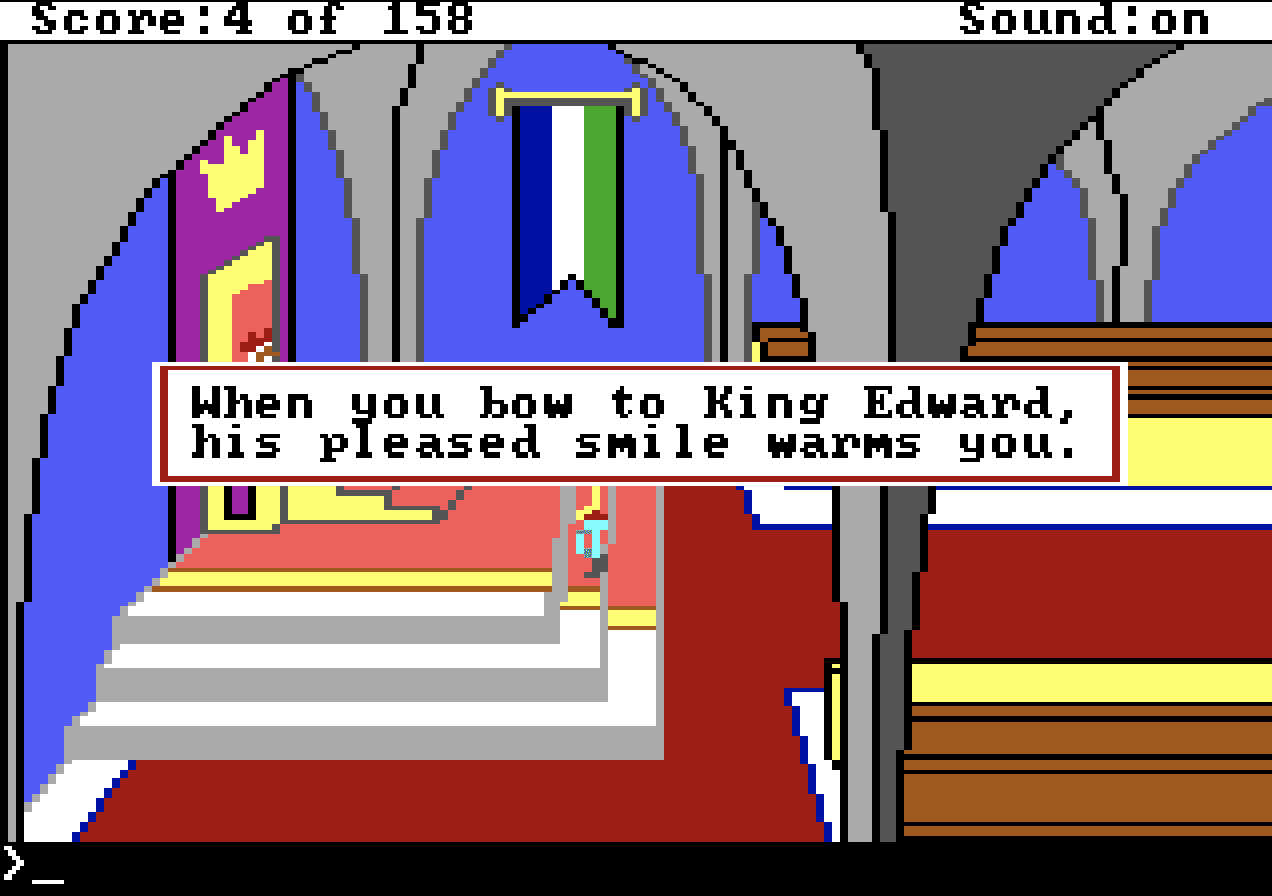

King’s Quest was Sierra On-Line’s first game to use the AGI (Adventure Game Interpreter) engine instead of the spreadsheet-based engine they’d used on their earlier adventures. This new programming language allowed for more animation, giving the appearance of a character walking around in a pseudo-3D environment. It was an extraordinary feat for the time, surprising even those inside the studio.

Much like Wizard and the Princess, King’s Quest took place in a vast fantasy world, with players exploring the Kingdom of Daventry. Taking control of the brave knight Sir Graham, you were required to retrieve three lost treasures for the ailing King Edward to prove yourself worthy of the crown. The adventure took Graham into a dragon’s lair, a witch’s den, and into the path of a terrifying ogre, with a single wrong move resulting in the knight’s untimely demise.

The game’s punishing difficulty made sense when you consider the audience Roberta was designing for – those who only bought one or two games a year. “The games weren’t supposed to allow you to just whip right through them,” she says. “You needed to out-think the designer [to win].”

5_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

5_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />Forget Dark Souls – this beanstalk is the true benchmark of video game difficulty.

The original King’s Quest was released on the PCjr in 1984, but had limited success due to the machine’s commercial failure. Luckily, Sierra On-Line kept the rights to both the game and the engine, so Ken was able to quickly negotiate other releases, including versions for the Tandy 1000 and Apple II.

King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown sold tremendously well, and sales climbed as the months went on. Plans for a sequel started almost straight away, with Roberta recognising the demand to know what happened next. “The huge sales, fan letters, and everyone asking for a sequel, all indicated that people liked [what we were doing],” she says.

“It was a game that people experienced with their families. We still hear from adults who remember playing King’s Quest with their parents and grandparents… it was the game for families of that era.”

Taking knives: always a surefire way to have a lot of fun.

Happily Ever After?

Family ended up being a key theme from then on. Following King’s Quest, the first three sequels introduced players to King Graham’s wife and kids. In King’s Quest II: Romancing the Throne (1985), King Graham meets his wife, the beautiful princess Valanice locked away in a tower by the evil witch Hagatha.

In King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human (1986), players control Gwydion, a boy later revealed to be King Graham’s long-lost son, Alexander. And in King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella (1988), players join Rosella as she sets off on her own adventure, travelling to the land of Tamir to find a magical fruit to save her sick father.

Each game brought new innovations. King’s Quest II was the first to prominently feature a soundtrack, with former music teacher and Sierra On-Line programmer Al Lowe stepping in as composer. This desire to innovate was what kept the series relevant and players interested, but it didn’t always result in the smoothest of development cycles.

3_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

3_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />Gotta love the time-honoured adventure game tradition of ‘finders keepers’.

King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella, in particular, was a tough project, with a cavalcade of problems conspiring to delay it. The story goes that during production Ken and Roberta asked Sierra On-Line systems engineer Jeff Stephenson for new features, including 256 colours (the AGI system only supported 16) and the ability to use CD-ROM drives and sound cards. Stephenson took this as an excuse to also throw out the existing adventure-game-specific language for a new object-oriented programming language in the new SCI (Sierra’s Creative Interpreter) engine.

“The benefits… were significant,” Stephenson says. “In the old AGI system, pretty much any sort of behaviour you wanted in the game first had to be programmed into the game system itself before it could be used to write the game. With a general-purpose language like SCI, the game developers could write the behaviour themselves – in the game, without any work in the engine.”

There was a problem, however. King’s Quest IV continued the tradition of being somewhat of a testing ground for new programmers at Sierra On-Line. The new team not only had to get used to the realities of working on and shipping a game, but had to familiarise themselves with a completely new language overnight.

2_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

2_.png” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />According to Al Lowe, Sierra On-Line “bet the company” on the success of King’s Quest IV.

As Lowe remembers, “In late August 1988, they called me in and said, ‘Will you take a look at this game? Roberta doesn’t think it’s going to be done in a month.’ And I looked at it and said, ‘It ain’t gonna be done in a year.’ So we called off every other game in the company. Every other game was put on hiatus and we all programmed King’s Quest IV for 30 days. And when I say 30 days, I mean 30 solid days like you would work until you couldn’t see any more…”

With the current conversations around crunch in the games industry and its effects on workers, it’s hard to hear comments like this from Lowe without flinching a little. Not only because of the impact this may have had on workers at the time, but because stories like this are still so depressingly familiar in an industry where innovation and passion often go hand in hand with terrible working conditions and excessive crunch. While it can be argued that the industry didn’t know any better at the time, it’s much harder to make the case for that now as the industry has become more formalised.

With all hands on deck, King’s Quest IV managed to release on schedule in 1988 and was another hit for the studio. King’s Quest V: Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder! followed in 1990, with a sequel, King’s Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow, releasing two years after.

Both games expanded on the King’s Quest formula, boasting gorgeous VGA graphics and the introduction of voice acting, referred to internally as ‘Mother Goose’, due to its connection to another game Roberta Williams had previously worked on called ‘Mixed-Up Mother Goose’.

2_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

2_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />King’s Quest V represented a huge graphical leap forward for the series, due to the introduction of VGA graphics.

The decision was also made to switch the game from a tried-and-tested parser system to a cursor system from King’s Quest V onwards – this came about after Roberta had witnessed her mother struggling to play her games. Ken assumed the change would inspire a flurry of hate mail, but in the spring 1991 issue of Sierra On-Line’s own InterAction magazine, he noted a mostly positive reception from fans of the studio. In the same issue, in fact, a parent wrote in with a story about their disabled son being able to complete their first King’s Quest game with the use of a modified mouse.

“We always wanted to add voices, better music, great animation, 3D, live actors, anything that would enhance the experience,” says Roberta. “Anything that would add realism, we did. Everything is a progression. As soon as the machines could handle something, we wanted to take advantage of it. When you can, you do.”

Following the success of King’s Quest V and VI, the King’s Quest series took a dramatic left turn with 1994’s King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride. The game eschewed the look of the previous two games for a cleaner, more Disney-like aesthetic. It was an attempt to push the envelope even further, using traditional hand-drawn techniques to create more elaborate worlds. But for some, it was too great a departure, and perhaps an attempt to ride on the coat-tails of the Disney renaissance that was also happening at the time.

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />King’s Quest VI featured a number of different endings depending on the actions you take.

“The art style was something Roberta wanted to do,” claims Mark Seibert, who was a producer on the project. He acknowledges the influence Disney films such as Aladdin and The Lion King had on the project, and remembers that Sierra On-Line contracted several different animation houses to help complete the scenes the project required.

This resulted in heavy delays as Seibert and his team had to co-ordinate with multiple studios to ensure the animation remained consistent. Says Seibert: “I recall going to work on a Monday morning one week and not going back home until Thursday afternoon – I think the team started a pool on when I might fall asleep at my desk.”

When asked about overtime at Sierra On-Line, Seibert recalls “it was often ‘mandatory’, but we always tried to avoid that as it can only go on for so long. King’s Quest games, or Roberta’s games, were often notorious for being behind schedule due to the high level of innovation involved. That often created a lot of unknowns that just couldn’t be scheduled. So many times, those of us on her projects just worked a little harder and later to get it done. I worked many 70- to 100-hour weeks during ‘crunch’ time.”

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />In King’s Quest VII, players joined both Valanice and Rosella on a perilous adventure.

Too Many Cooks

Today, King’s Quest VII remains something of an oddity for those revisiting the series, as does King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity. Between the release of King’s Quest VII and the start of development on the next King’s Quest game, there were huge changes at Sierra On-Line. The biggest being that Ken and Roberta sold Sierra On-Line to the e-commerce company, Comp-U-Card.

It was under these peculiar circumstances that King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity was developed, with Roberta remaining at the company to try and complete the project. She refers to its development now as “an involuntary team effort”, while Ken notes that Roberta grew increasingly upset at having her ideas and suggestions ignored, often coming home in tears.

According to Ken, while he was at the company, he was an important intermediary between Roberta and the programmers, convincing them to try and accomplish her more “impossible” ideas. Without him there, her bargaining position was significantly weakened and as a result, she was unable to push her ideas as well as she had in the past.

King’s Quest VIII is arguably the black sheep of the family.

King’s Quest was also being developed on an external engine for the first time, created by Dynamix. As Seibert recalls: “Unfortunately, they weren’t developing the engine specifically for King’s Quest, and so our goals weren’t always the same. After about a year, we chose to take the engine code to Seattle and finish it ourselves. This put us significantly behind.”

The initial plan for King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity was to make a 3D action-adventure, and continue the ‘movie-like’ approach they’d established with Phantasmagoria while introducing some lite-RPG mechanics. Players controlled a new character, Connor, who must rise to the occasion when King Graham and his family are turned to stone.

For many players, King’s Quest VIII was a somewhat disappointing end to a revolutionary series. For years after its release, rumours swirled about a potential sequel or reboot, but all attempts came to nought. That is, until August 2014, when rights holders Activision announced that indie studio The Odd Gentlemen was working on a revival. A love letter to King’s Quest, it acted as both a sequel and a retelling of the series’ events. Released episodically, the game was about family, succession, and managed to tie a neat bow on the series almost 30 years after it began.

“For us, the main concern was making sure the Williamses felt we had done their property justice,” says Evan Cagle, the art director on 2015’s King’s Quest. “When we showed it to them, and they were excited about it, we knew we were on the right track.”

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />

3_.jpg” alt=”” width=”1920″ height=”1080″ />The first episode of King’s Quest (2015), A Knight To Remember, recounts the events of King’s Quest 1 and how Graham became king.

According to Cagle, development was far from easy. The team had gone for an ambitious hand-painted art style, so to prepare for future episodes, they had to create all the requisite assets prior to releasing episode one. During development, however, they soon realised the need for more assets to prevent repetition.

This caused some notable delays in between episode releases, which combined with Activision’s lack of marketing – and the decision to restrict the Epilogue’s availability to the Complete Collection release – stacked the odds against it succeeding. There’s been no news of a new King’s Quest since The Odd Gentlemen wrapped development on King’s Quest in 2016; Activision later abandoned its relaunch of the Sierra On-Line brand, leaving its future uncertain.

As for Ken and Roberta, they’re both retired, though they still speak fondly of their time with the series and continue to receive mountains of emails and letters from fans. For now, King Graham’s journey is at an end. But with the King’s Quest series still loved by so many, there’s always the chance that another adventurer will one day take on the mantle.