At its core, even defining what is and isn’t a time-loop game is difficult, but let’s try. “The time-loop game is any game where, upon death or running out of time etc., both the game world and the player are returned to an earlier moment from which they relive the experience with the benefit of foreknowledge”, perhaps.

Far from being satisfactory, this makes Halo mechanically a time-loop game. End me with a Covenant sniper rifle, and I am reset to the last ‘Checkpoint’. There, I’m at an earlier point in time, destined to live/die repeatedly until I figure out which rock that damn sniper is behind so I can shoot them first. Could adjusting my definition to include a fixed starting point, such as always waking up by the campfire in Outer Wilds at the exact same point in time, help? Be careful, since this would still include roguelikes such as FTL or Hades, and it’s also easy to imagine a time-looping game where the player can, through the loops, unlock new ‘starting points’ in the game world’s time and space.

To loop, or not to loop?

Games such as these might more accurately be “a game wherein the player and game world are returned to an earlier point in time upon running out the clock or death, but the fiction remains aware of events in those discarded timelines”. Where I stand, it seems this would satisfy just about any existing time-loop media. Every Day the Same Dream, Groundhog Day, and Russian Doll would be boring if there wasn’t an awareness of the time-loop and ability to remember what happened in previous loops: Bill Murray would, just like everyone else in that town, repeat the same actions endlessly. Factor in player agency in video games, though, and you create a new possibility, where time loops back on itself and every character is totally unaware, but the player remembers the discarded timelines and can use their awareness to foresee threats and try new things. Is it possible, then, that one could view the majority of video games as bizarre bastardisations of the time-loop format wherein nobody but the player perceives the world resetting?

2019 even saw the release of a canonical sequel to Groundhog Day in a VR time-loop game subtitled Like Father Like Son.

Intrinsically, this produces a psychic disconnect between player and character, since the player is almost always better informed than the character is. Cyclic games will naturally emerge then, closing the player-to-character gap, as we try to innovate in narrative design and preserve the player’s delicate suspension of disbelief, wherein some element of the fiction, usually the player character, is aware of the cut-short timelines. And so we arrive at DEATHLOOP and The Forgotten City, but there’s still distinctions to be made. Its setting may be cyclical, but DEATHLOOP does not feature looping in its narrative mechanics.

Beyond combat/exploration, the actual tale of Colt and Julianna at the heart of DEATHLOOP does not repeat, as both recall the events of the previous loops. This series of conversations progresses only ever forwards, and since the player can’t make any narrative decisions in the game, they are not able to use any prescient knowledge to manipulate the narrative mechanically.

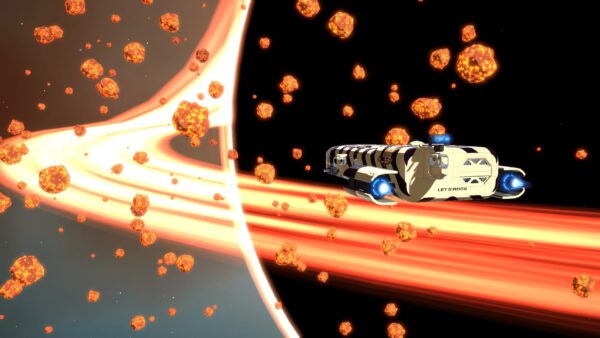

DEATHLOOPDEATHLOOP: looping action, but surprisingly straightforward narrative design.

Visions of the future

Writer Nick Pearce sits on the other side of this divide with The Forgotten City. To this end he features explicit narrative decision-making heavily, using a dialogue framework inherited from Skyrim, and almost all of his characters have no knowledge of the time-loop. Say something anachronous, and it leads to new story and dialogue branches that only reveal themselves on subsequent loops. If the player likes, similar to Bill Murray’s shortcut-like manipulation of those around him in Groundhog Day, they’re able to awaken and immediately say exactly the right things to convince City’s loveliest character, Galerius, to prevent several imminent catastrophes. That very same loop, you may be relieved of a significant amount of gold by a conman, then in the next loop new dialogue options appear, allowing the savvy player to take advantage of his time-reset obliviousness and con him right back, deliciously weaponising his own previous phrasing against him.

The Forgotten City: the player character can use their memory of previous timelines to undermine conversations in interesting new ways.

Yet even beyond what appears in City, the looping story format seems to afford us new opportunities. Is it possible to use time-looping to create uniquely isolated characters, as the only people able to perceive the loop, or could we use it to treat people as ‘levels’ to be ‘solved’? Existing free from always having individual conversations be ‘done in one’, we can perhaps create characters who are much harder to ‘navigate’; more obstinate, or more complex.

It also creates challenges: The Forgotten City can’t help but reintroduce cognitive distance between the player and their character when the writer, understandably, can’t keep up with the breadth of volume of potential things the player may want to say to each character; it becomes slightly restrictive in the final act, as dialogue options about ‘looped’ revelations which we feel should be present are absent.

I believe time-looping games exist on a spectrum. It could be argued that time-looping play of some sort is present in many or even most games, even though the fiction of a time-loop isn’t. Not much further along the spectrum sit games whose fictions contain a looping nature, although this doesn’t necessarily mean that all aspects of gameplay feature looping. At the far end, there could be games where every factor is intrinsically cyclic, but it’s beyond me to say if that yet exists. I think not.

Elsinore: this retelling of Hamlet through a time-loop is probably the most ambitious piece of time-looping writing in games. It’s well worth your time.

Dissonance? What dissonance?

To reconcile the fact that, due to failure and retrying, the player often knows about events coming up in games that their character is oblivious to, player effort is often expended to role-play not having that knowledge. But this is still then undermined by in-game challenges such as ‘bosses’ which you are intended to fail at a few times, gaining foresight, before you succeed. Could this be intertwined with the historic propensity for mute, ‘blank slate’ protagonists in games? Much easier to overlook a disconnect between player and character when the character never draws attention to themselves.